See also: http://www.geocities.com/CapitolHill/Lobby/9362/gauck/indexmoo.html

| The above graphic (Das Jahr 1989) is [was] on the

first page of the Gauck officials

homepage website, the BStU.

The federal commissioned agency in charge of researching the files

of the state security apparatus of the former GDR - commonly called

the Gauck-Officials, since it is led by Joachim Gauck, an ardent

anti-communist Christian. Mr. Gauck claims that already as

a 9 year old boy he realized that socialism was an unjust

system. The graphic says it all. One is reminded of scenes from

Schindler's List, or any of the pictures that bring home the horrors

of the Holocaust. The cold faced guards at night on one side are

presented facing the innocent threatened masses on the other side.

While this was the rule in Nazi Germany, aside from the border

regime, it was not the rule in former East Germany. It

is, however, indicative of most Germans to overstate the

inhumanities of the East German regime in order to play down

or "relativize" the horrors of the Holocaust. The

overstating of the inhumanities of the East German regime serves not

only the desire to play down, but even to "justify"

Nazism (Nazism serving as a counterweight to "Jewish

Bolshevism") as this recent

article in the New York Times illustrates:

"Relativizing" the Holocaust |

Click

here for a few pictures of what

East Germany was not!

| No amount of degrading

humiliation is spared in a constant act of comparing the former East

Germany with Hitler's Third Reich! Particularly

repugnant have been the comparisons that were made comparing the

Jewish leader of the PDS (the reformed totally democratic

former ruling East German Party), Gregor Gysi, with Nazi criminals

such as Joseph Göbbels, Hitler's propaganda minister, and Hans

Globke, the official commentator to the Nuremberg race laws (in

the case of Joseph Göbbels by none other than the then practicing finance

minister Theo Waigel).

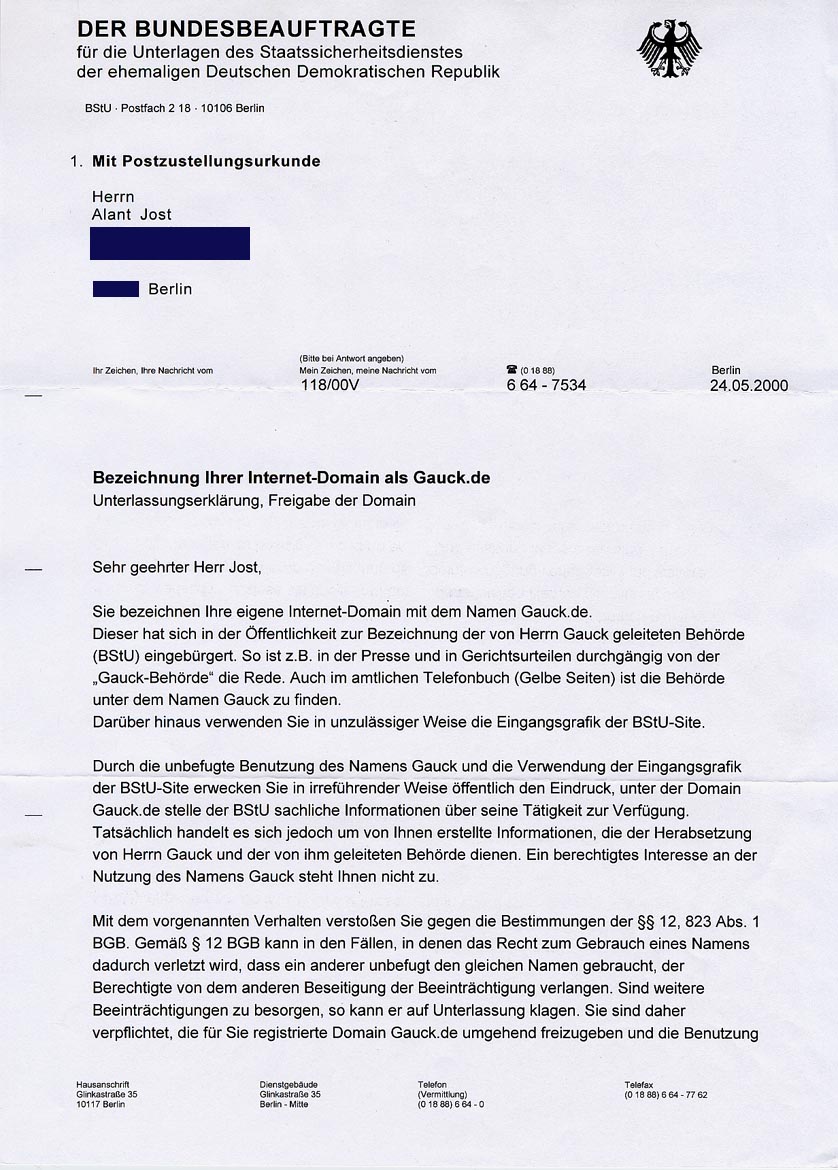

The attempt by the "Gauck-Officials" to assassinate Mr. Gysi politically by struggling to denounce him as a "Stasi spy" led me to acquire the domain name Gauck.de as a means of documenting the Gauck-Officials relentless attempts at destroying him politically. As a result, the German court in Berlin has forbade me to register or use ANY TOP LEVEL domain with "Gauck" in it. Since, I will not voluntary relent my right to protest in this way, I am forced to carry many thousands of Marks of lawyer's fees, and face penalties from the state and possible imprisonment. The ruling by the court effectively sets a precedent that would allow Hitler (if he were living today) to outlaw a critique of his politics using a domain name such as Hilter.de, Hitler.com, Hitler.org, Hitler.net, Hitler.co.il (domain for Israel), or any possible combination of Hilter.xxx or Adolf-Hitler.xxx. This ruling is not only a violation of my intellectual property rights, but an attempt to curtail dissent and free speech. |